Psychedelics

As a scientist,

I believe that psychedelics are among the most fascinating substances there are.

Their unique mind-altering capabilities have major significance for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. At the same time, they hold the key to one of mankind’s greatest riddles: our consciousness.

Over the last decade, much attention has been drawn to psychedelic drugs which propelled to the forefront in research on consciousness and mental disorders. This “psychedelic renaissance” follows a lengthy period with little to no publications on the topic, lasting from the introduction of the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances in 1971 until the turn of the century.

-

One of the most notable synthetic psychedelics, lysergic diethylamide acid (LSD), was discovered in 1938 by Swiss chemist Albert Hoffmann, who identified its psychedelic properties in 1943 through self-ingestion. Among the first to research these novel compounds was the British psychiatrist Humphry Osmond, who coined the term psychedelic (from greek psyche “mind” and deos “revealing”) in the late 50s. He aided Aldous Huxley during a mescaline trip in 1952, who manifested his experience in “The Doors of Perception“, widely regarded as one of the most prominent accounts of the psychedelic experience. Huxley described a disconnection of his perception as “the percept swallowed up the concept” and felt liberated from “the world of selves, of time, of moral judgments and utilitarian considerations, the world (and it was this aspect of human life which I wished, above all else, to forget) of self-assertion, of cocksureness, of overvalued words and idolatrously worshipped notions.” In 1957, the American banker and amateur ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson travelled to Mexico and met the Mazatec healer María Sabina who introduced him to psilocybin-containing mushrooms. The story became published in Life magazine under the title “Seeking the Magic Mushroom” and introduced a large audience to psychedelics.

In the 60s and 70s, psychedelics, particularly LSD (sold under the trade-name Delysid by Sandoz) became increasingly popular among psychiatrists for the treatment of numerous conditions including depression, anxiety disorders, autism and alcohol addiction. Large-scale trials such as the Spring Grove experiment and others lead to hundreds of papers being published on the topic and the outlook on psychedelics as an established therapeutic agent seemed promising. Albeit the surge in research interest, it must be noted that these studies often lacked proper controls and were poorly designed. Simultaneously, American psychologist Timothy Leary, who himself conducted experiments with psychedelics at Harvard University, became a leading figure of the hippie anti-war movement in the 60s and 70s and popularized the recreational use of psychedelics within the “counter-culture” as a means to increase creativity, spirituality and connectedness.

The widespread use of psychedelics and other psychoactive substances by the movement motivated Richard Nixon’s “War on Drugs” and the Controlled Substance Act (CSA) in the 70s. The UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances declared psychedelics as Schedule 1 drugs in 1971, being dangerous and unsuitable for therapy, despite hundreds of studies showing the opposite. This led to a near-complete halt of psychedelic research which lasted over three decades until the turn of the century.

The “Psychedelic Renaissance” involved numerous impactful studies at new research centres, particularly in the US, UK, Netherlands and Switzerland. These include the first functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) studies with psychedelics, as well as well-controlled studies on their therapeutic potential, augmenting the already promising findings of the last century. While psychedelics emerged during a period of heightened support for psychoanalysis, our understanding of psychiatry benefited tremendously through the rise of cognitive neuroscience and neuropsychopharmacology.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy may bridge the gap between classical psychoanalysis and cognitive neuroscience. Despite little changes in drug regulations and little support from pharmaceutical companies, public attitudes have shifted as the knowledge of drugs increased.

-

Psilocybin is a classic psychedelic and tryptamine alkaloid found in more than two hundred mushroom species often called “magic mushrooms”. It was first synthesized in 1958 by Albert Hoffman at Sandoz.

Upon ingestion, psilocybin is rapidly phosphorylated to form psilocin, which shows structural similarities to serotonin (5-HT). Doses between 12-20 mg of peroral psilocybin and blood plasma levels of 4–6 mg/ml are sufficient to cause psychedelic effects in most individuals. Effects peak around 90 min after peroral administration, with effects lasting up to 5 hours9. The psychedelic effects of psilocin are mediated by 5-HT2A receptor agonism, a common characteristic among psychedelics. While psilocin and other psychedelics are non-selective and bind to a variety of 5-HT receptor agonists, the potency of psychedelics is correlated with their affinity to the 5-HT2A receptor subtype. Blocking of the 5-HT2A receptor using the antagonist ketanserin stops the effects of psychedelics.

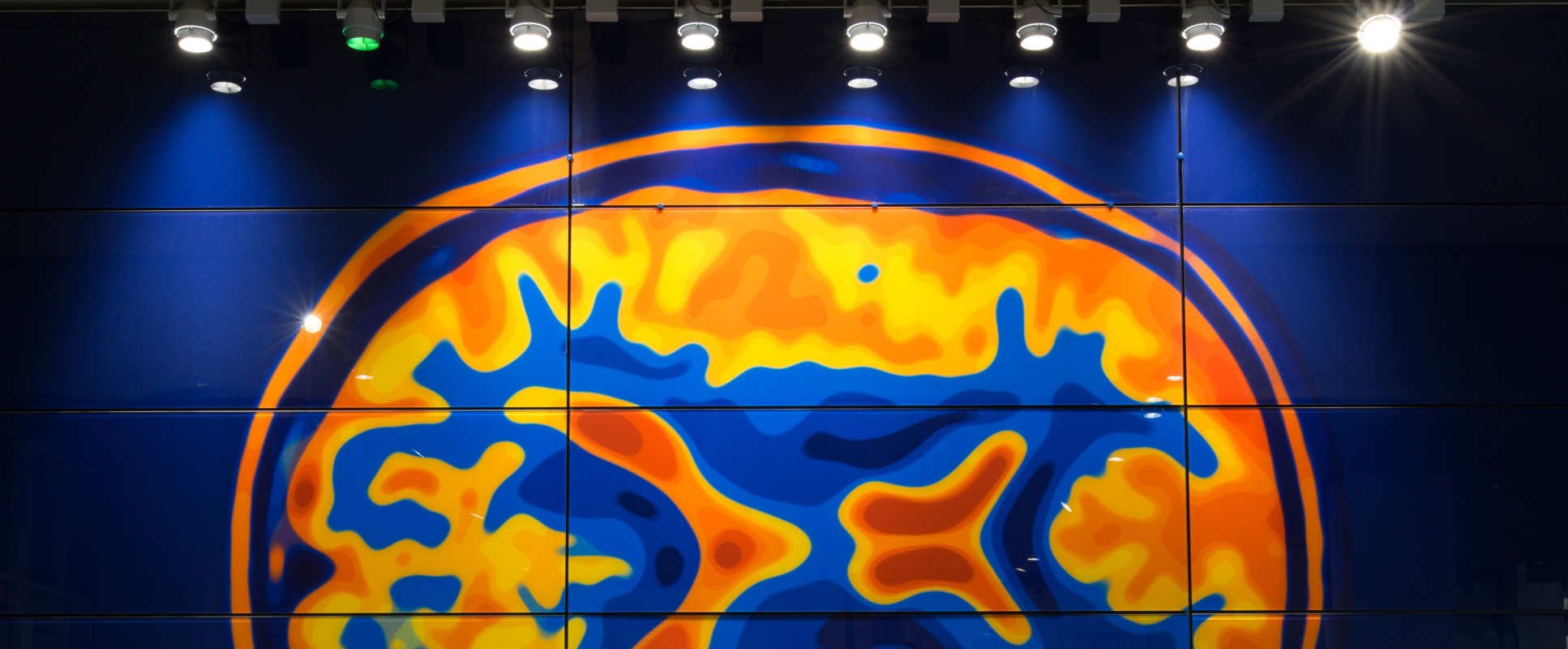

The 5-HT2A receptor is most abundant in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). These are key areas of the default mode network (DMN), a densely connected network involved in self-reflection, mind-wandering, mental time travel and commonly referred to as the “seat of the ego”. Rumination (“overthinking”) is strongly associated with major depressive disorder and is linked to hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the DMN. Psychedelics downregulate the DMN, which may explain ego dissolution, disruptions of entrenched thought patterns and positive treatment outcomes.

-

Studies on psilocybin have demonstrated its ability to reduce tobacco addiction, alcohol dependence, suicidality and psychological distress. Studies on major depressive disorder, the leading cause of disability worldwide, have shown particularly promising outcomes. With as little as one to two doses of psilocybin along with psychological support, symptoms of treatment-resistant depression were reduced for up to six months post-treatment. Psilocybin may thus potentially be the most powerful intervention for depression to date. Further, studies on both healthy subjects and patients show long-lasting increases in well-being, personality and worldview including (decreased) neuroticism, extraversion, openness, connectedness (e.g. from self, others), acceptance (of emotion), nature relatedness and anti-authoritarianism. These effects are thought to be mediated through disruption of “hard-wired”, entrenched thought patterns that are reinforced in e.g. depression.

Psilocybin acutely increases plasticity and connectivity, decreases cerebral blood flow (predominantly in the thalamus), and enhances activity in sensory cortices during autobiographical recollection. Beyond psychedelic effects, activation of central 5-HT2A receptors is thought to be involved in enhanced learning, cortical plasticity, cognitive plasticity, anxiolytic and antidepressant effects.

At the Centre for Psychedelic Research, I had the privilege to work with the world’s leading researchers in the field.

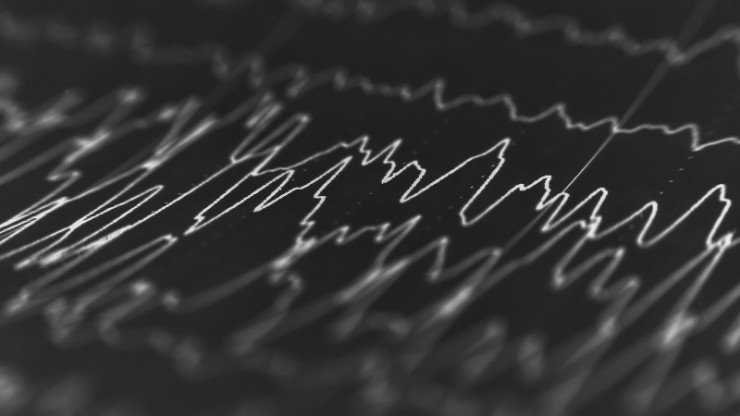

As a Postgraduate Researcher, I was involved in a study investigating the effects of Psilocybin on EEG brainwaves and psychological outcomes.

Psilocybin & EEG Brainwaves

In contrast to 1 mg, 25 mg Psilocybin acutely decreased EEG activity in the Theta, Alpha and Beta band and increased activity in the Gamma Band. Concurrently, Lempel-Ziv entropy increased. Significance is indicated as <.05 (red dot). Abbreviations: BL, baseline; LZs , Lempel-Ziv Complexity; LD, low dose; HD, high dose.

Decreases in alpha activity and increases in entropy reflect a switch from Top-Down to Bottom-Up sensory processing and an altered state of consciousness, which is thought to be a key driver of psychological effects observed under psychedelics.

Psilocybin & Psychological Insight

Even after 4 weeks, a single administration of psilocybin lead to increased scores on the Psychological Insight Scale, a measure of self-awareness and self-reflection. Sidak tests revealed p<.001 for all time points (n=26).

The acute effects of a single psilocybin dose translate into long-term psychological effects on insight.

Publications

Effect of Psilocybin on neural oscillations and signal diversity in EEG

The scientific nitty-gritty of my research.

Psychedelics for Psychotherapy

The current landscape of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

Psychedelics:

Effect on Brain and Psychology

How psychedelics affect us in the way they do — in laymen’s terms.

Psychoactive Mushrooms for Neuroenhancement

On the use of psychedelic mushrooms for micordosing.

Want to hear more?

Let’s talk.

REFERENCES

Heal, D.J., Henningfield, J., Frenguelli, B.G., Nutt, D.J., and Smith, S.L. (2018). Psychedelics - Re-opening the doors of perception. Neuropharmacology 142, 1–6.

Sessa, B. (2016). The history of psychedelics in medicine. Handbuch Psychoaktive Substanzen. Springer Reference Psychologie. Berlin: Springer.

Huxley, A. (1952). The doors of perception. Mental 98, 2–24.

Gordon Wasson, R. (1957). Seeking the Magic Mushroom. LIFE.

Wark, C., and Galliher, J.F. (2010). Timothy Leary, Richard Alpert (Ram Dass) and the changing definition of psilocybin. Int. J. Drug Policy 21, 234–239.

Belouin, S.J., and Henningfield, J.E. (2018). Psychedelics: Where we are now, why we got here, what we must do. Neuropharmacology 142, 7–19.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Muthukumaraswamy, S., Roseman, L., Kaelen, M., Droog, W., Murphy, K., Tagliazucchi, E., Schenberg, E.E., Nest, T., Orban, C., et al. (2016). Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 113, 4853–4858.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Leech, R., Hellyer, P.J., Shanahan, M., Feilding, A., Tagliazucchi, E., Chialvo, D.R., and Nutt, D. (2014). The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 20.

Passie, T., Seifert, J., Schneider, U., and Emrich, H.M. (2002). The pharmacology of psilocybin. Addict. Biol. 7, 357–364.

Halberstadt, A.L., and Geyer, M.A. (2011). Multiple receptors contribute to the behavioral effects of indoleamine hallucinogens. Neuropharmacology 61, 364–381.

Glennon, R.A., Teitler, M., and Sanders-Bush, E. (1992). Hallucinogens and serotonergic mechanisms. NIDA Res. Monogr. 119, 131–135.

Vollenweider, F.X., Vollenweider-Scherpenhuyzen, M.F., Bäbler, A., Vogel, H., and Hell, D. (1998). Psilocybin induces schizophrenia-like psychosis in humans via a serotonin-2 agonist action. Neuroreport 9, 3897–3902.

Kometer, M., Schmidt, A., Jäncke, L., and Vollenweider, F.X. (2013). Activation of serotonin 2A receptors underlies the psilocybin-induced effects on α oscillations, N170 visual-evoked potentials, and visual hallucinations. J. Neurosci. 33, 10544–10551.

Ettrup, A., Holm, S., Hansen, M., Wasim, M., Santini, M.A., Palner, M., Madsen, J., Svarer, C., Kristensen, J.L., and Knudsen, G.M. (2013). Preclinical safety assessment of the 5-HT2A receptor agonist PET radioligand [ 11C]Cimbi-36. Mol. Imaging Biol. 15, 376–383.

Erritzoe, D., Frokjaer, V.G., Haugbol, S., Marner, L., Svarer, C., Holst, K., Baaré, W.F.C., Rasmussen, P.M., Madsen, J., Paulson, O.B., et al. (2009). Brain serotonin 2A receptor binding: relations to body mass index, tobacco and alcohol use. Neuroimage 46, 23–30.

Weber, E.T., and Andrade, R. (2010). Htr2a Gene and 5-HT(2A) Receptor Expression in the Cerebral Cortex Studied Using Genetically Modified Mice. Front. Neurosci. 4.

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S., and Ford, J.M. (2012). Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 8, 49–76.

Zhou, H.-X., Chen, X., Shen, Y.-Q., Li, L., Chen, N.-X., Zhu, Z.-C., Castellanos, F.X., and Yan, C.-G. (2020). Rumination and the default mode network: Meta-analysis of brain imaging studies and implications for depression. Neuroimage 206, 116287.

Johnson, M.W., Garcia-Romeu, A., Cosimano, M.P., and Griffiths, R.R. (2014). Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. J. Psychopharmacol. 28, 983–992.

Bogenschutz, M.P., Forcehimes, A.A., Pommy, J.A., Wilcox, C.E., Barbosa, P.C.R., and Strassman, R.J. (2015). Psilocybin-assisted treatment for alcohol dependence: a proof-of-concept study. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 289–299.

Hendricks, P.S., Thorne, C.B., Clark, C.B., Coombs, D.W., and Johnson, M.W. (2015). Classic psychedelic use is associated with reduced psychological distress and suicidality in the United States adult population. J. Psychopharmacol. 29, 280–288.

Friedrich, M.J. (2017). Depression Is the Leading Cause of Disability Around the World. JAMA 317, 1517.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C.M.J., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., Bloomfield, M., Rickard, J.A., Forbes, B., Feilding, A., et al. (2016). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry 3, 619–627.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Roseman, L., Bolstridge, M., Demetriou, L., Pannekoek, J.N., Wall, M.B., Tanner, M., Kaelen, M., McGonigle, J., Murphy, K., et al. (2017). Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 7, 13187.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Bolstridge, M., Day, C.M.J., Rucker, J., Watts, R., Erritzoe, D.E., Kaelen, M., Giribaldi, B., Bloomfield, M., Pilling, S., et al. (2018). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology 235, 399–408.

Erritzoe, D., Roseman, L., Nour, M.M., MacLean, K., Kaelen, M., Nutt, D.J., and Carhart-Harris, R.L. (2018). Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 138, 368–378.

Lyons, T., and Carhart-Harris, R.L. (2018). Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J. Psychopharmacol. 32, 811–819.

MacLean, K.A., Johnson, M.W., and Griffiths, R.R. (2011). Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. J. Psychopharmacol. 25, 1453–1461.

Watts, R., Day, C., Krzanowski, J., Nutt, D., and Carhart-Harris, R. (2017). Patients’ Accounts of Increased “Connectedness” and “Acceptance” After Psilocybin for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 57, 520–564.

Kettner, H., Gandy, S., Haijen, E.C.H.M., and Carhart-Harris, R.L. (2019). From Egoism to Ecoism: Psychedelics Increase Nature Relatedness in a State-Mediated and Context-Dependent Manner. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16.

Carhart-Harris, R.L. (2018). The entropic brain - revisited. Neuropharmacology 142, 167–178.

Petri, G., Expert, P., Turkheimer, F., Carhart-Harris, R., Nutt, D., Hellyer, P.J., and Vaccarino, F. (2014). Homological scaffolds of brain functional networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 11, 20140873.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Leech, R., Williams, T.M., Erritzoe, D., Abbasi, N., Bargiotas, T., Hobden, P., Sharp, D.J., Evans, J., Feilding, A., et al. (2012). Implications for psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: functional magnetic resonance imaging study with psilocybin. Br. J. Psychiatry 200, 238–244.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Erritzoe, D., Williams, T., Stone, J.M., Reed, L.J., Colasanti, A., Tyacke, R.J., Leech, R., Malizia, A.L., Murphy, K., et al. (2012). Neural correlates of the psychedelic state as determined by fMRI studies with psilocybin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 2138–2143.

Ly, C., Greb, A.C., Cameron, L.P., Wong, J.M., Barragan, E.V., Wilson, P.C., Burbach, K.F., Soltanzadeh Zarandi, S., Sood, A., Paddy, M.R., et al. (2018). Psychedelics Promote Structural and Functional Neural Plasticity. Cell Rep. 23, 3170–3182.

Zhang, G., and Stackman, R.W., Jr (2015). The role of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in memory and cognition. Front. Pharmacol. 6, 225.

Madsen, M.K., Fisher, P.M., Stenbæk, D.S., Kristiansen, S., Burmester, D., Lehel, S., Páleníček, T., Kuchař, M., Svarer, C., Ozenne, B., et al. (2020). A single psilocybin dose is associated with long-term increased mindfulness, preceded by a proportional change in neocortical 5-HT2A receptor binding. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol.

Carhart-Harris, R.L., and Nutt, D.J. (2017). Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. J. Psychopharmacol. 31, 1091–1120.